By Dr. Gene P. Gengelbach, Ph.D., P.A.S.

Fall is the time of year many people associate with colorful foliage and football. For the livestock producer, this is the time of year they must evaluate their forages and devise a feeding strategy for the upcoming winter months. Many parts of the country experienced drought conditions for a large part of the summer and early frosts or freezes may have prematurely ended the growing season, as well. There are a number of challenges when feeding forages affected by drought or frost, among these are high nitrates, prussic acid, and decreased yield/quality.

Nitrogen is generally taken up by the plant in the form of the nitrate ion (NO3-). It is then reduced to nitrite (NO2-) and finally to ammonia (NH3), which is incorporated into amino acids to build protein molecules. It takes energy to convert nitrate to nitrite, so if normal growth is interrupted by drought, frost, or even prolonged cool, cloudy weather nitrates can accumulate within the plant. Application of high levels of nitrogen fertilizer or manure can make the situation worse. Plants known for accumulating nitrates are corn, small grains, sorghums (including sorghum-sudangrass crosses), and many perennial grasses. Weeds like pigweed, Johnsongrass, nightshade, and lambsquarters are also nitrate accumulators.

Nitrates will diminish if normal growth resumes, so wait seven to 10 days after a drought-ending rain to harvest or graze, and wait five to seven days after a killing frost. Ensiling can reduce nitrate levels by as much as 40 to 50%. Try to harvest high-nitrate forages as silage/haylage whenever possible, treat with Silo King® to ensure proper fermentation, and wait at least 21 days before feeding. Nitrates tend to be highest in the stem or stalk of the plant, especially the lowest portion. Raising the cutter-bar to at least 10-12 inches will help reduce nitrate concentrations in corn or sorghum silage.

Ingestion of high levels of nitrates can be toxic to animals, causing abortions, illness, and even death. As in the plant, nitrates in the rumen are converted to nitrites and then ammonia. The conversion of nitrite to ammonia is relatively slow, allowing nitrites to build up. Excess nitrite is absorbed into the bloodstream. Nitrite converts hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells) to methemoglobin, which is unable to transport oxygen to the tissues and the animal dies because of lack of oxygen.

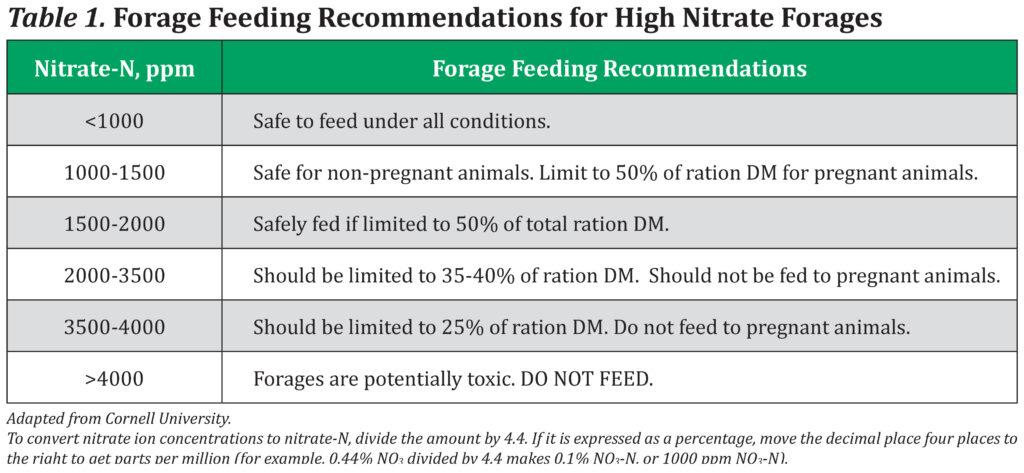

Nitrate poisoning is characterized by panting, excessive salivation, a weak and rapid heartbeat, muscle spasms, incoordination, and frequent urination. Mucous membranes will be discolored and the blood turns a dark, chocolate-brown color in severe cases, followed by death. All forages should be tested for nitrates before they are added to the ration. Nitrate levels are generally reported either as nitrate ion (NO3) or nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N), expressed as a percentage of dry matter or as parts-per-million (ppm).

Pregnant or breeding females are particularly susceptible to nitrates. Oxygen flow is reduced to the fetus or ovaries, causing abortions or irregular heats. For those animals, it is recommended to keep NO3-N intake below 400-500 ppm in the total ration. Always add Micro XX® at the recommended rate when feeding rations high in nitrates.

It is best to introduce high-nitrate forages gradually into the ration. Never turn hungry cattle out onto pastures where high nitrates are expected. Wait until after they have had a chance to fill up on “safe” forages or TMR. Be sure to limit grazing time and monitor animals closely.

Prussic acid or hydrocyanic acid (HCN, or hydrogen cyanide) can be found in toxic levels in several plant species. This is especially true in the sorghum family (grain sorghum > Johnsongrass > forage sorghum > sorghum-sudangrass > sudangrass), choke cherry, and black cherry. Young, rapidly-growing plants and plants stressed by drought, frost, or hail are most likely to contain high concentrations of HCN. Here are some general guidelines to help prevent HCN poisoning:

Here are some tips for harvesting and feeding drought-stressed corn silage:

Forages in Feedlot Diets, Balancing Nutritional Components

Transition Cows: Nutrition and Inflammation

Can Grain/Starch Utilization Be Improved In Your Herd

B Vitamins – Not on the B-Team Anymore

What is Milk Urea Nitrogen and What Does It Say About the Cow